Christianity and the Body Count Problem, Part II:

Why ‘He Gets Us’ Fails, Taylor Swift Threatens, and Anthropology Holds the Key to Christianity’s Future

But if the salt loses its saltiness, how can it be made salty again? It is no longer good for anything, except to be thrown out and trampled underfoot.

Matthew 5:13-14

This is the second part in a series exploring Christianity’s self-measurement problem. Here’s the first part in case you missed it:

Christianity and the Body Count Problem I.

“God blessed them and said to them, “Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea, the birds in the sky, and every living creature that moves on the ground.”

In my previous article, I argued that the real indicator of Christianity’s health isn’t church attendance or self-reported identification. It’s birthrates. Higher birthrates reflect who truly lives their faith, ensuring its sustainability over generations.

In this article, I approach the same issue from another angle, addressing a deeper, existential crisis: Christianity has lost its tribal identity. Without a strong sense of tribe—an embodied, distinct community—Christianity struggles to reproduce itself culturally and spiritually.

Here’s how this article will unfold:

Case Study: Taylor Swift and the Threat to Christian Identity

Why Modern Christian Strategies Fail

Social Science Insights on Identity Formation

Early Christianity as a Model of Tribal Identity

Proposed Solution: Reclaiming a Distinct, Embodied Tribal Identity

This essay may challenge our modern assumptions about Christianity. Yet, as I’ll show, reclaiming tribal identity may be the key to the faith’s survival and flourishing in the secular age.

“Many Such Cases”

This past month, Swifties took a hit. Not only was Taylor Swift’s new boyfriend Travis Kelce’s team dethroned, but Swift herself was loudly booed at an NFL game. It was a cultural moment—enough for Glamour magazine to condemn it as proof of “right-wing misogyny.”

This booing followed a legendary troll move last October where a Florida man flew a MAGA banner over Taylor’s concert, openly mocking her childlessness.

The reactions to the open animosity conservatives have thrown at her are wild—ranging from accusations of sexism to women literally divorcing their husbands.

Why is Taylor Swift such a political lightning rod? Plenty of celebrities have castigated the MAGA movement and have not received such vitriolic treatment.

Plenty of celebrities have bashed MAGA without such backlash. No one’s losing their minds over Beyoncé or Drake. Why not? Because they’re not pretending to be anything other than elites. They own their elite status—behavior, beliefs, aesthetics, and all.

But Taylor Swift is different. She embodies the feminine “hicklib” archetype. In other words, she is a progressive wrapped in the aesthetics of small-town America. She’s the girl next door in jeans, flannel, and cowboy boots; her songs romanticize trucks, high-school love, and Americana. Her Netflix documentary is literally titled “Miss Americana,” and with Travis Kelce, they’ve become media darlings, labeled “quintessential American sweethearts.”

But when you mess with people’s identity, you better believe they'll swing back. Swift marketed herself as an all-American, country girl-boss who drove trucks, loved ball games, and grew up Christian only to openly reject and mock the very values that identity holds dear.

Taylor and Kelcy both have taken on these personas as American archetypes, but they use their platform to advocate for values that oppose archetypically American values.

Real country folk vote for Harris

This alone is enough to infuriate conservatives, but Taylor’s all-American “skinsuit” strikes at the heart of American evangelical identity. Swift openly tries to redefine Christianity:

Christians are actually hateful bigots:

Real Christians are pro-choice:

Real Christians are Pro Witchcraft

Mocking Christians as a Christian is Cool, Too

“I just learned these people only raise you

To cage you

Sarahs and Hannahs in their Sunday best

Clutchin’ their pearls, sighing, ‘What a mess.’

Just learned these people try and save you

‘Cause they hate you.”

But Daddy I Love Him

Swift’s behavior is classic left-wing “infiltrate and redefine”—or better yet, “hijack and hollow out.” Progressivism’s most effective propaganda tactic is hijacking familiar terms:

“Social Justice” → Unrestricted immigration, anti-white racism

“Choice” → It’s your choice to kill a baby

“Misinformation” → Any idea progressives dislike

“Education” → Ideological indoctrination

This tactic is devastating because it doesn’t just change words it destroys identities by leaving behind a hollowed-out shell that progressives then fill with meaning that serves its own goals.

By claiming the “Christian, home grown, American sweetheart” label, Taylor redefines those identities—Christianity isn’t faith in Jesus anymore; it’s progressivism. It’s "In This House" signs on your lawn instead of actual Christian identity.

This explains why anger at Taylor runs deep. Intentional or not, she threatens flyover America’s Christian identity. Social science shows that when a group’s identity is threatened, its high identifiers double down—like the Florida man who flew the MAGA banner. Meanwhile, low-identifiers might dilute their distinctiveness by accepting that one can be Christian and pro-choice and eventually merging completely into secular culture (Spears, Doosje, & Ellemers, 1997).1

Thus, Christians and conservatives are right to be wary of posers like Swift. They represent a corrosive force to tribal coherence, reducing Christianity from a powerful identity to a meaningless label.

One online comment captured this perfectly:

No Boundaries, No Tribe: How ‘Christian’ Became an Empty Label

Swift isn’t an isolated example; she represents a massive segment of self-identified Christians today. A shocking 2022 Lifeway Research survey found that 43% of evangelicals no longer believe Jesus is divine.2 This means nearly half of so-called evangelicals deny the most fundamental belief of Christianity. Such statistics expose a crisis: the label “Christian” is becoming empty and meaningless.

Allowing Swift and millions like her to redefine what it means to be Christian is dangerous, not because we need perfect purity, but because without clear boundaries, tribal identity disintegrates. Christianity isn’t just a private belief; it's about belonging to Christ’s distinct tribe. But a tribe without non-negotiable beliefs has no identity.

I’m not advocating that we exclude people out of self-righteousness; this is simply about preserving the integrity of what it means to be Christian. Emphasizing Christ’s divinity as non-negotiable isn’t “mean.” It's essential for tribal survival. Without this, Christianity risks dissolving into meaningless labels that offer no identity at all.

We cannot afford to be passive about heresy and what I call “soft apostasy.” I don’t mean we should condemn, but we need to invite people to make a clear “in or out” choice. A meaningful tribe requires meaningful boundaries.

Christianity’s Three Failed Strategies Against Secularism

Christian leaders typically use three main strategies to respond to the secular erosion of Christian identity symboled by the Head, the Heart, and the Feet. Each, however, is deeply influenced by Enlightenment liberalism, which elevated individualism, rationalism, and egalitarianism as core values. But here’s the problem: you can’t fight liberalism on liberalism’s turf. Accept its premises, and you're forced into its conclusions. The inevitable conclusion of liberalism is disenchantment and the blending of all people into androgynous biomass.

Yet, Christian leaders keep attempting these half-measures.

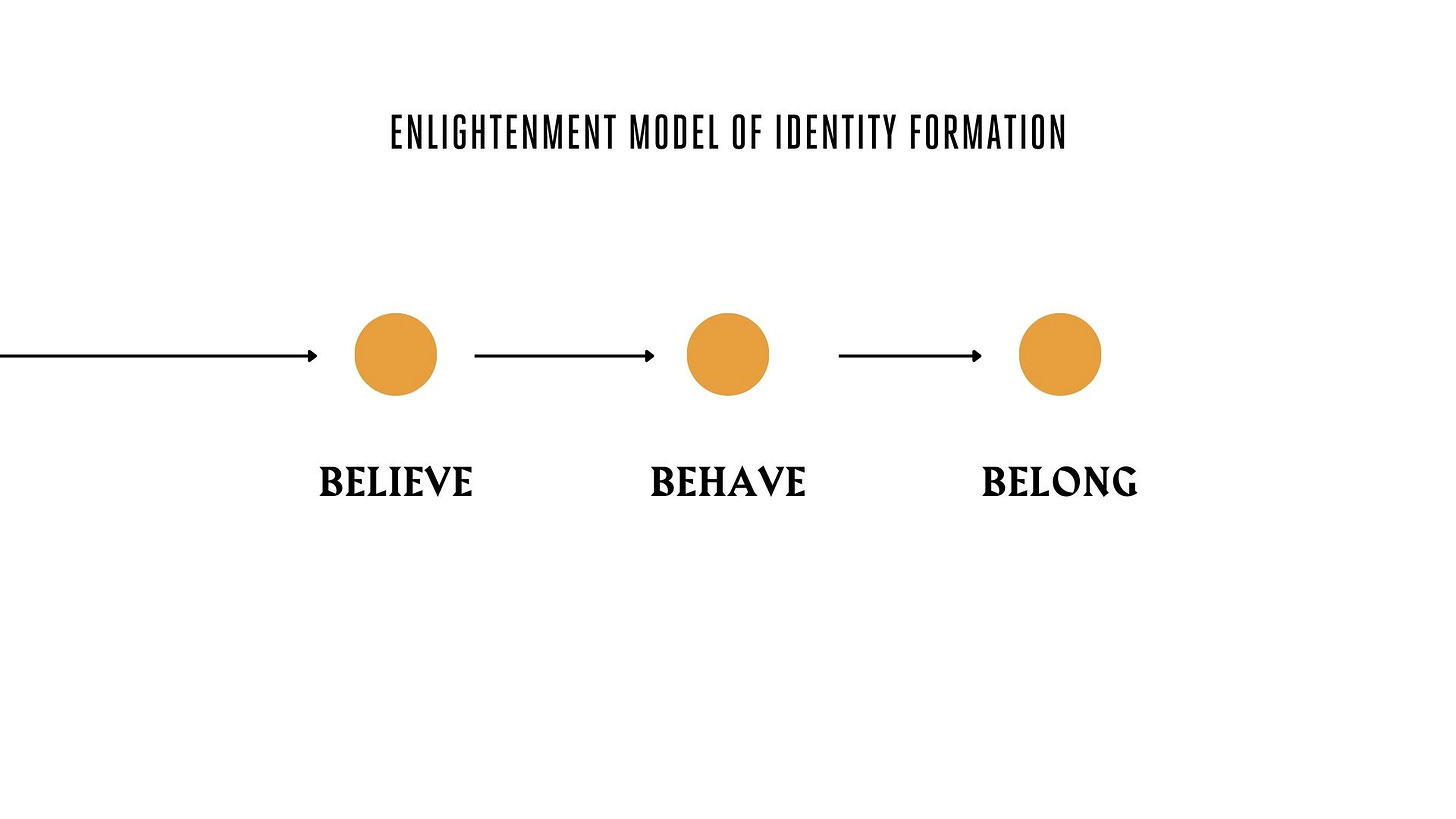

The head (rational Christianity)

Common in orthodox, intellectual circles, this approach treats Christianity primarily as intellectual belief. A bishop hires an agency to create slick catechetical content, or a misguided billionaire funds another “God’s Not Dead” sequel, hoping that correct doctrine leads to right behavior and eventually a strong community. But facts and doctrines alone rarely transform people deeply enough to build real, tribal identity.

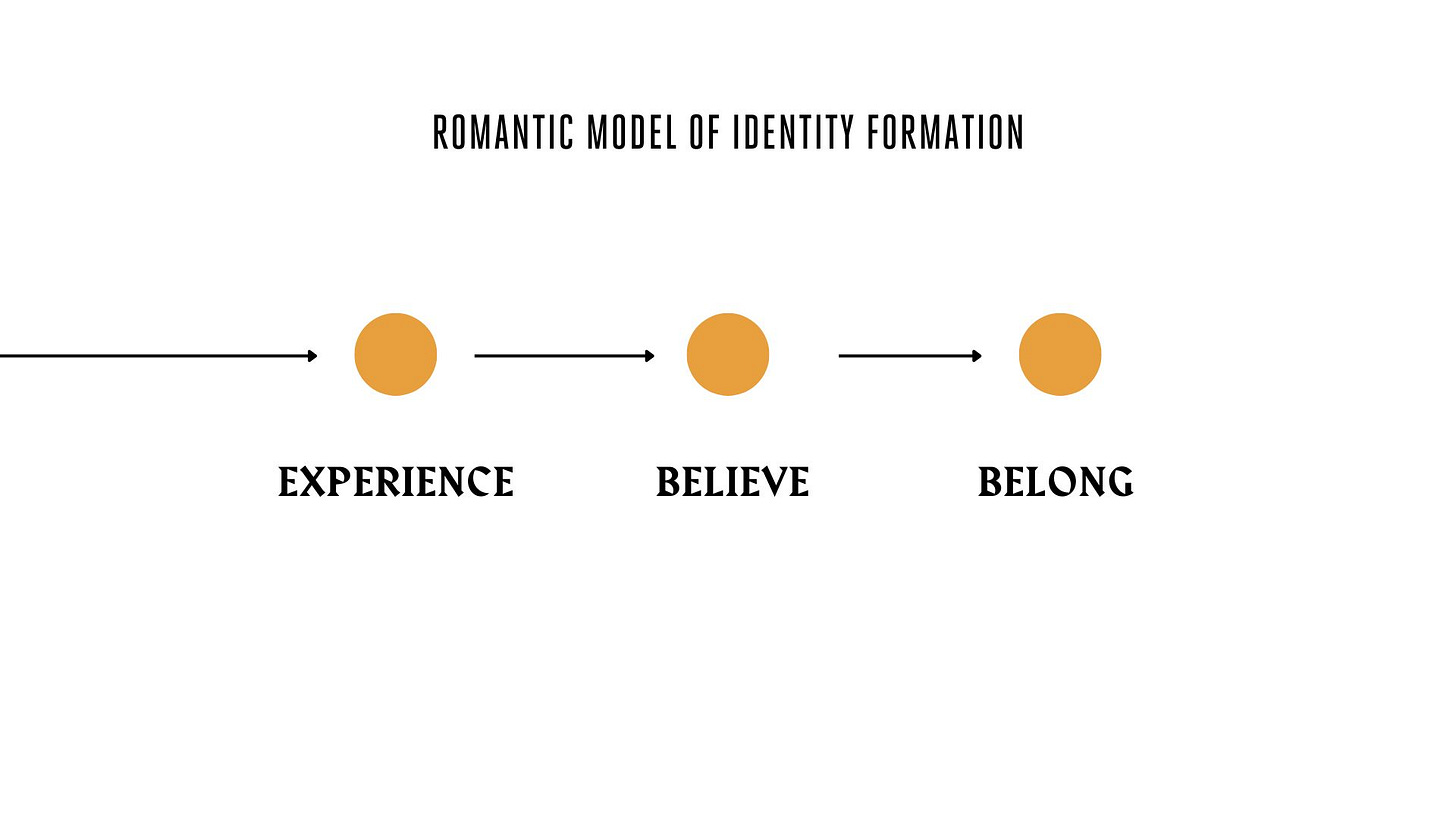

The Heart (Individualistic Christianity)

This approach flips the script: it promotes experience first, then belief, and finally behavior. Rooted in romanticism, it’s the domain of megachurches and youth groups. Imagine flashy worship bands, drummers flying over congregations, and pastors who condemn “dead religion.” It feels good but is often shallow, creating followers who lack a deep, communal identity.

The Feet (Egalitarian Christianity)

The social action approach—think of Christianity as good Samaritanism, epitomized by the “He Gets Us” Super Bowl ads or churches flying pride flags. You’ll hear slogans like “Come as you are,” “You belong here,” or “We do life together.” Christianity is an egalitarian social club, open to all and exclusive to none. But identity requires boundaries. Without them, this approach often dilutes Christianity into a vague set of lovely ideas or empty slogans, leaving no distinct tribe to belong to.

The Real Way Identity Formation Works

Now, don’t get me wrong—all three approaches (head, heart, and feet) have their place. But they miss something huge: human beings just aren’t fundamentally rational, individualistic, or egalitarian. Those ideas sound great (thanks, Enlightenment philosophers!), but they don’t hold up under scientific scrutiny. Humans are more complicated—and frankly, more tribal—than that.

Let me break it down. Modern research shows three key truths about identity:

Identity formation is pre-rational (gut-level, not logical).

All identity is tribal (mimetic, not individualistic).

All tribes are hierarchical and status-driven (sorry, egalitarians).

Identity is Pre-rational

In the ‘70s, social psychologists Henri Tajfel and John Turner ran some famous experiments—known as the “minimal group experiments.” They randomly assigned boys to groups based on trivial differences, like their taste in abstract paintings, and asked them to distribute points (money) between their group and another. Anyone who has ever played any game before should intuitively recognize what happened: Despite the arbitrary nature of these groups, the boys consistently favored their own group (Tajfel et al., 1971).3

Key takeaway: These kids didn’t think their way into loyalty. They instinctively favored their own group. This proves identity formation is natural and automatic, preceding rational justification (Turner et al., 1979).4

All Identity is Tribal

Rene Gerard was one of the preeminent scholars of our age. His life’s work was essentially to reveal that desire, and therefore, all human behavior is mimetic. "Man is the creature who does not know what to desire,” he wrote, and “he turns to others in order to make up his mind. We desire what others desire because we imitate their desires."5

Every social experiment that has tested group behavior not only reinforces Gerard’s theory but takes it further. Individual identity is shaped by group identity. To name a few:

Asch Conformity Experiments

Participants were asked to judge line lengths in a group where others intentionally gave wrong answers. Most participants denied their own perception and conformed to the group’s incorrect judgments (Asch, 1956).6

Stanford Prison Experiment

Participants randomly assigned as “guards” or “prisoners” quickly adopted extreme behaviors characteristic of their roles. Guards became authoritarian, prisoners submissive. Participants entirely lost sight of their individual identities as they were absorbed into the roles assigned to them (Zimbardo, 1971).7

Robbers Cave Experiment

Boys at a summer camp divided into two groups quickly developed intense group rivalries. Individuals fully adopted their group's competitive desires, even developing open hostility toward the other group. Name-calling, verbal aggression, and physical confrontations became common. One group raided the other's cabin, overturning beds and stealing personal belongings, purely driven by rivalry. Even during joint activities like watching movies, boys insisted on sitting apart, loudly jeering or booing the opposing group. These behaviors demonstrated how quickly individual identities became overshadowed by fierce group identity and competition (Sherif et al., 1961).8

Thus, not only are our desires mimetic, but our very identity is fundamentally social, a function of group values rather than emanating from the individual’s private soul. In other words, we don’t ask, “Who am I?” but rather, “Who am I compared to them?”

All Tribes Are Hierarchical and Status-driven

Finally—and this might sting for liberals—tribes aren’t egalitarian; they’re always intensely hierarchical. Social Identity Theory states groups seek “positive distinctiveness”—academic jargon for “we want to be better than them.” This status competition is fundamental to the process of identity formation (Tajfel & Turner, 1979).9 In other words, human behavior is shaped by the pursuit of “positive status” or “honor, "and the fear of the loss of status, or “shame.”

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt summarizes it bluntly: “Humans are ultra-social animals...tribal and groupish creatures who crave hierarchy and status” (Haidt, 2012).10 There seem to be no activity too dangerous, strenuous, or punishing to engage in in order to achieve honor and avoid shame (rituals, sacrifices, hazing). Anthropologist Joseph Henrich found this universal—across cultures and organizations, from Amazonian tribes to modern corporations (Henrich, 2016).11

Thus, all three liberal core beliefs about human nature, that humans are rational, individualistic, and egalitarian, are false. Tribalism isn’t a backwards system enforced upon innocent people; rather, Tribe is the foundation of human nature. Strategies that ignore these principles are doomed to failure.

Given this anthropological reality, what would proper identity formation look like?

It must assume tribal dynamics (in-group vs. out-group).

It must incorporate a status hierarchy (clear ranks and roles).

It must be embodied—meaning identity forms through real-time feedback loops and status signaling (discipleship).

In other words, real identity formation isn’t abstract—it’s gritty, messy, and life on life. This is something modern Christianity has almost entirely overlooked.

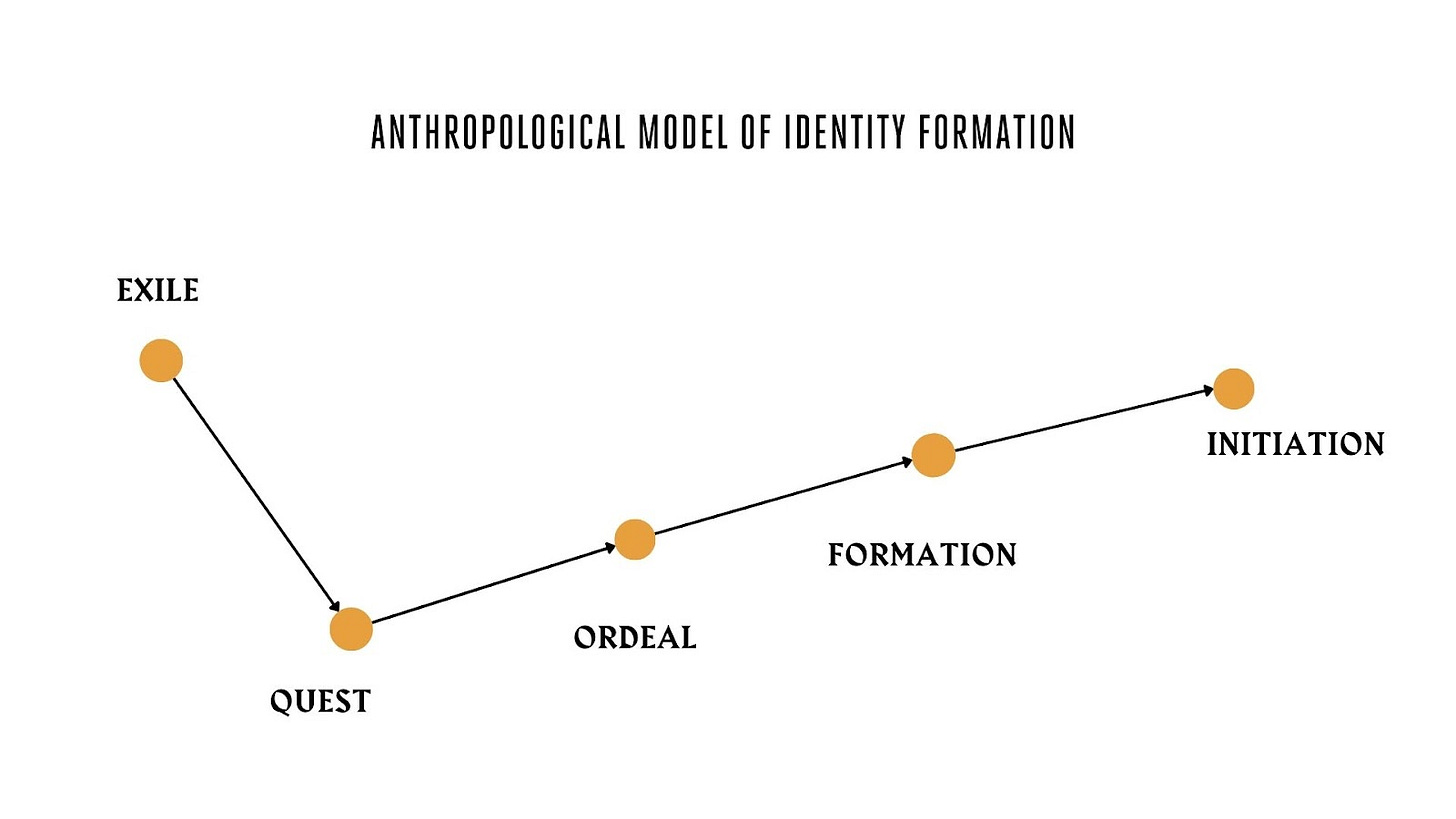

How Identity Formation Actually Works: The Tribal Pattern

Identity formation follows a surprisingly consistent tribal pattern. This pattern is nothing like modern Christianity’s current approaches. It begins with exile, moves through a quest and ordeal, and finally ends in formation and initiation. Let’s unpack this.

Exile: Identity Starts with Loss

Nobody looks for a new identity when life’s going great. An alcoholic doesn’t walk into AA just because he's bored. We search for a new identity when the old one fails us—when the pain of staying the same outweighs the fear of change.

Psychologists refer to the experience of losing a core aspect of one's identity, such as through divorce, job loss, relocation, or personal crisis, as "identity disruption." This disruption can lead to significant psychological distress as individuals struggle with a fragmented sense of self and diminished life satisfaction.

Moreover, social exclusion or isolation has been shown to activate the same neural regions associated with physical pain. Research indicates that experiences of social rejection engage the same areas of the brain that activate during physical pain. Thus, fear of exile or loss of status profoundly impacts our overall well-being and often catalyzes the search for a new identity, which, as we have already shown above, is not an internal, private process.

Quest: Testing New Identities

After exile, we start a quest for belonging. Think of it as identity shopping, but deeper. Sociologists call this “identity exploration” (Marcia, 1966).12 We experiment and “try on” different communities, groups, and roles, seeing which one clicks. This phase involves active searching, immersing ourselves in various tribes until we find a “fit.”

Ordeal: The Test of Belonging

But here’s the catch: a new identity in a new tribe isn’t free—it’s earned. Joining a new tribe isn’t like buying a jacket; it's more like walking into a social war zone. Every group—from middle-school skaters to ancient religious communities—has unspoken rules and tests.

Anthropologists have documented this across cultures: scarification rituals among the Nuer in Sudan, fraternity hazing in America, and military boot camps.13 Victor Turner (1967) called this phase communitas—the intense shared hardship where outsiders are tested and broken down so that they can be reconstituted as insiders if they prove worthy.

Formation: Learning the Tribe’s Language

Passing the ordeal grants entry, but real identity formation happens afterward. Now you must learn and adopt the group’s behaviors, values, and beliefs—a process psychologists call “social learning” (Bandura, 1977).14 This is mimetic behavior; you imitate and absorb the tribe’s norms not just to fit in, but to gain recognition, respect, and rank.

Status hierarchies motivate members to deeply embrace the tribe’s identity (Tajfel & Turner, 1979).15 It’s not just about belonging; it’s about achieving status within the group, reinforcing your commitment.

Initiation: Officially "One of Us"

Initiation is the tribe’s formal recognition: “You’re one of us now.” If the ordeal proves you belong, initiation officially welcomes you. Turner called this aggregation—the initiate is re-integrated into the community with a new, official identity. Initiation often involves rituals—a baptism, a new name, access to secrets, or a seat at the table. These rituals reinforce identity repeatedly and publicly, ensuring the tribe’s culture survives across generations.

Why Modern Christian Strategies Fail

In summary, this tribal model completely contradicts all three Christian strategies (head, heart, feet) mentioned earlier. Faith is not primarily a private, rational, or charitable pursuit, though these each might play a role. Most Christians today would feel highly uncomfortable suggesting evangelization or Christian initiation should look anything like the model suggested above. That would be “exclusionary and unkind,” they’d say.

Yet, this is exactly how the early Church did it. And it’s precisely why early Christianity didn’t just survive. It conquered the world instead.

Early Christian Initiation: A Tribal Model

Let’s take a look at how the early Church approached identity formation—it was intensely tribal, embodied, and communal, nothing like the abstract conversions we imagine today.

Quest: Seekers didn't just join; they entered the catechumenate, undergoing years of deep formation—not just memorizing doctrines, but actively practicing the Christian life within a tight-knit community.

Ordeal: Becoming Christian wasn’t easy. Membership required rigorous tests of commitment—exorcisms, fasting, and even public renunciations of your old life. Belonging was earned, never assumed.

Formation: Once accepted, newcomers fully adopted the tribe’s shared behaviors and beliefs. The early Church had a clear, enforced hierarchy: Apostles, bishops, priests, deacons. Some behaviors had high status (e.g., martyrdom, like Stephen), while others were low status (e.g., the drunken orgies Paul criticizes in Galatians).

Initiation: This whole process culminated in the Easter Vigil, where converts underwent Baptism, Confirmation, and Eucharist—rituals marking full tribal membership. It was a profound, public recognition: “You’re officially one of us now.”

Enforcing Norms: The early Church wasn’t shy about strictly enforcing group norms. Public confession, penance, and even excommunication were used to maintain unity, identity, and boundaries.

Contrary to modern assumptions, the early Church didn’t just “convert” individuals—it formed a tribe. And this was exactly what Jesus intended. When asked who his mother and brothers were, Jesus pointed to his disciples and said:

“Here are my mother and brothers. For whoever does the will of my Father in heaven is my brother and sister and mother.” (Matthew 12:48–50)

This model of Christian initiation was comprehensive, embodied, and holistic. It honored human nature—tribal, hierarchical, communal—while pointing it toward heaven.

Testing the Theory

Now, if all of this is true, you’d expect the Christian groups today that most closely resemble this tribal model—those that are distinct, hierarchical, and least egalitarian—would be the ones growing fastest. Meanwhile, the groups that are the most inclusive, least distinct, and most egalitarian would be shrinking rapidly.

Why Not Having an Identity Means Not Having Members

Here's the hard truth: We believe because we belong—not vice versa. Belonging isn't just about hanging out with congenial, like-minded people at church picnics; it's about recognizing “I'm like these people, and not like those people.” Tribal belonging requires clear boundaries, shared rituals, communal practices, and a collective identity that visibly sets insiders apart from outsiders.

Modern Christianity—whether it’s a set of abstract doctrines, emotional worship experiences, or even social justice campaigns—will always fail to build a true identity if it continues to ignore this tribal reality. Identity isn’t forged by winning debates or emotional highs; it’s forged by participation in a distinct, embodied community that demands sacrifice and offers real belonging in return.

If the Church wants a robust, lasting Christian identity, it must stop obsessing over “what people should believe” and emphasize “who they must become.” That transformation doesn’t happen in isolation or through intellectual persuasion alone. It happens in real community, with shared practices, rituals, clear expectations, and—yes—even some blood, sweat, and tears. We need communities willing to say: “This is who we are. This is who we are not.”

Compare the He Get’s Us Superbowl ad to this powerful concept alternative:

It does the opposite of vague, inclusive messaging. It demands everything. It offers a distinctive identity, honor, and pride. Unsurprisingly, it has half a million more likes than the lukewarm “He Gets Us” Super Bowl ad that it’s mocking. One ad offers real belonging; the other offers nice feelings. The difference is tribal identity.

Ultimately, as theologian J. Gresham Machen wrote:

“Involuntary organizations ought to be tolerant, but voluntary organizations, so far as the fundamental purpose of their existence is concerned, must be intolerant or else cease to exist.”16

To survive and thrive in this secular age, Christianity must regain its distinctiveness, the willingness to enforce boundaries, and the confidence to be unapologetically itself. Otherwise, it risks becoming exactly what the secular world wants it to be: irrelevant, inoffensive, and ultimately, extinct.

Let’s choose differently. Let's choose tribal identity, real belonging, and a Christianity that isn’t just surviving, but thriving—because it knows exactly who it is.

So, what’s next? In my final installment, I’ll tackle the big questions: What exactly is the Christian tribe—and how should it behave? And don’t worry, I won’t say anything too wild—I’m a sensible centrist, after all.

I just want the public school system razed to the ground and replaced with communities educating their own children in their own culture. I want Christian culture to reclaim dominance in every institution—from Hollywood to Harvard.

Nothing too crazy.

Spears, R., Doosje, B., & Ellemers, N. (1997). "Self-stereotyping in the face of threats to group status and distinctiveness: The role of group identification." Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(5), 538–553.

Lifeway Research, “The State of Theology,” 2022.

Tajfel, H., Billig, M., Bundy, R. P., & Flament, C. (1971). "Social categorization and intergroup behaviour." European Journal of Social Psychology, 1(2), 149-178.

Ibid, 179

Girard, R. (1987). Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World. Stanford University Press.

Asch, S. E. (1956). Studies of independence and conformity: A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 70(9), 1–70.

Zimbardo, P. G. (1971). The power and pathology of imprisonment. Congressional Record (Serial No. 15, October 25, 1971).

Sherif, M., Harvey, O. J., White, B. J., Hood, W. R., & Sherif, C. W. (1961). Intergroup conflict and cooperation: The Robbers Cave experiment. University of Oklahoma Book Exchange.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). "An integrative theory of intergroup conflict." In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations (pp. 33-47). Brooks/Cole.

Haidt, J. (2012). The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. Pantheon Books.

Henrich, J. (2016). The Secret of Our Success: How Culture Is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter. Princeton University Press.

Marcia, J. E. (1966). "Development and validation of ego-identity status." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3(5), 551-558.

Turner, V. (1967). The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. Cornell University Press.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. Prentice-Hall.

Turner, V. (1969). The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Aldine Publishing.

Machen, J., (2011). Christianity and Liberalism, 166.

I swear, you might be the only Catholic in the entire country who is (1) charismatic enough to be worth listening to, (2) understands the fundamental importance of vibes, and (3) is capable of teaching how to use vibes in a systematic way to create belonging.

Thanks for this article Marcellino! Enjoyed reading your thoughts on the struggles of Christianity in the modern world.

I was particularly struck by your claim that Christianity must be exclusive or risk becoming irrelevant. I always find it quite amusing that it is people who don’t really have any connection to the Church, who blame the Church’s problems on being overly exclusive (exclusive claims on truth, exclusive towards homosexuals, exclusively ordaining men, etc.). In other words, they want the Church not to offend them, but would never show up on Sunday regardless.

I think this raises a real question though - is there a way that an intolerant organisation (one that makes exclusive truth claims) can form a civilisation? (viz., the Mechan quote: "Involuntary organizations ought to be tolerant, but voluntary organizations, so far as the fundamental purpose of their existence is concerned, must be intolerant or else cease to exist.") That is to say, can we in fact build up a Christian culture, or does it have to remain a voluntary organisation? I’m inclined prima facie to agree with Paul Kingsnorth et al. that Christian civilisation is oxymoronic. The Church does best when it’s a hated minority (blessed are you, when they revile you for my name’s sake).

But, at a certain point, the Church stopped being a voluntary organisation and started including essentially everyone (the occasional atheist intellectual or Jewish suburb being the exceptions that prove the norm). Somehow this succeeded for about a thousand years (if we ignore the splits between Catholicism, Orthodoxy, and Protestantism - and those were usually societal, rather than individual). Christendom only really collapsed in the last half of the 20th century.

If Christendom was an involuntary organisation, how did it manage to have such a long and successful run?